In previous blogs, I wrote about why exercise is important and what types of exercise are recommended. In the final part of this series, I will explore how to get more exercise (in everyday busy life) and how to know if you are getting enough.

Stress-Enhancing Mindset

For some, the very thought of exercise is stressful. For others, the idea of adding one more thing to an already-overpacked schedule brings on angst. Exercise itself is a stressor to the body (though, importantly, is also a great stress reliever to the mind). Negative health repercussions of high levels of unremitting stress in modern life have led many to believe that stress is something to be avoided at all costs. The stress I personally experienced during the pandemic certainly made me think so. It turns out, however, that some stress is actually good for you (for short, excellent videos on this topic, check out Stanford’s Rethinking Stress Toolkit). Stress is connected to things you care about, like your loved ones or your profession. Stress can help you focus your energy on things that really matter to you, pushing you to accomplish things you may not have thought possible.

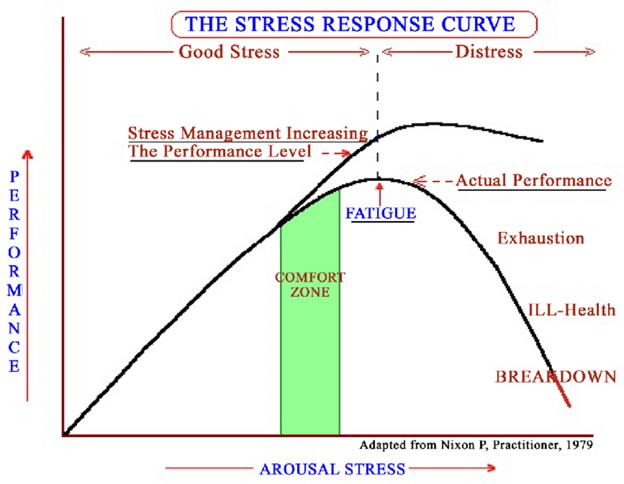

Like many things, the effects of stress on your body and performance occur on a continuum. In other words, the consequences of stress vary significantly depending on dose and duration. When you have little or no stress, you are bored. As stress starts increasing, so does your performance. When stress forces you out of your comfort zone, you can reach your maximum potential. Prolonged stress without a break or periods of high-intensity stress can lead to symptoms (muscle tension, palpitations, sleep disorders) and ultimately can cause burnout.

The trick, for both improving your physical performance as well as mental performance, is to embrace stress as a tool for enhancing your performance – in physical activity and in life. For more on the benefits of stress on cultivating a growth mindset, listen to this interview with Alia Crum, a leading researcher in this field from Stanford: Science of Mindsets for Health & Performance.

SMART Goals

If you are ready to increase your physical activity, it helps to make a plan. SMART goals can serve as a framework for thinking about what you want to accomplish, identifying your strengths and weaknesses, providing motivation, and keeping you focused. Research shows that the best time to make a positive change is during a significant life event, a “fresh start”, like moving to a new home, starting a new job, or getting married. If you’ve ever set a New Year’s resolution, you understand the benefit of wiping the slate clean to pursue a new goal.

A SMART goal is Specific, defining what you will do and how. For example, if you’re new to exercise, your goal should not be to “start exercising” but rather to aim for achieving the minimum amount of recommended cardiovascular activity a week (150 minutes). Framing this goal in a positive light is more effective than setting a goal to avoid something. For example, you will be more successful in achieving a goal to “move your body more” than setting a goal to “watch Netflix less.”

A SMART goal is Measurable. To be successful, it’s important to monitor your progress. This can be done using a tracking device (like a Fitbit, Oura ring, or Apple Watch) or even pen and paper.

A SMART goal is also Achievable. Be realistic, but don’t sell yourself short. If you’re sedentary, the goal of running a marathon at the end of a month is likely not a reasonable one. However, setting this as your ultimate goal is fine – just break down your lofty goal into smaller chunks achieved over time to improve your success. In fact, lofty goals are good. Research suggests it’s better to push yourself a little in your goal-setting as long as you build in leeway for the inevitable hectic intrusion of life. For example, you might set a goal to exercise 30 minutes a day but give yourself 2 “passes” a week rather than setting a goal that is too easy (like exercising 5 minutes a day or once a week).

A SMART goal should be Relevant – it should speak to your purpose. If you align your goal with something that is meaningful to you, it will help motivate you to do it. Rather than strength training because a doctor told you it’s good for your bones (which it surely is), your purpose may be to become stronger so that you can get up off the floor when you play with your grandkids.

Finally, SMART goals should be Time-Bound. Your goal may be to ramp up your exercise to 150 minutes a week in the next month (or 6 months, or year). When you reach that goal, you can set the next one for 200 minutes.

How to Increase Exercise in General

The simplest way to be more active is to find active things that you love to do (like hiking, kayaking, or pickleball) and do more of them. There are added health benefits if your chosen activity is outside – being in nature can improve wellness. Pick an activity you enjoy, that takes 20 minutes or more, uses most of your muscles, and increases your heart rate. Finding someone to exercise with (a “nudge”) can help keep you accountable (as can the social connection of participating in a group class). Add music for rhythm (there are apps that can determine the beats per minute (bpm) of songs you love so you can match your activity to the beat). Finally, exercising at the same time every day may help you establish a routine. (Atomic Habits, by James Clear explains how small changes can add up to major shifts in health).

How to get more Aerobic Activity

Despite health experts’ recommendation of 2.5 hours a week of moderate to vigorous physical activity, 2/3 of Americans struggle to achieve this goal. Finding time to commit to exercise during the busy work week is a barrier for many. If this is you, don’t despair! A study published in JAMA this July showed that even exercise by ‘weekend warriors’ can cut CV risk. After analyzing accelerometer-based physical activity data of nearly 90,000 people, researchers concluded similar cardiovascular risk reductions (including atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure) over a 6.3 year period in people who worked out only 1-2 days a week (weekend warriors) compared to regular exercisers. For those unable to achieve 2.5 hours of activity, though, researchers still urge as much exercise as possible. Every minute counts.

NEAT

Modern society lacks physical activity integration into daily life. This is an expected consequence of leaving the farming field to work at a desk, jumping in cars for errands rather than walking, and spending much of our leisure time in front of screens. It’s this decrease in daily movement that demands an increase in exercise to maintain health. But what if we could increase movement in some of our daily activities, too? Adding movement back into a relatively sedentary lifestyle, particularly when carving out 30 minutes for exercise isn’t possible, is another way to improve health (There’s a way to get healthier without even going to a gym. It’s called NEAT). NEAT (non-exercise activity thermogenesis) is the energy you need just to think, breathe, and sit upright, and includes all the calories you burn through daily living excluding exercise, sleeping, and eating.

NEAT encompasses things like yard work, household chores, walking in a store, typing, stretching, and even fidgeting. NEAT often burns more calories than exercise. Adding more steps in your day (7000-8500 is considered the sweet spot by many) is an easy way to increase activity. NEAT should not replace exercise, which has a myriad of health benefits (see Why Exercise?). Rather, the advantage of NEAT lies in its accessibility. Increasing NEAT can be as simple as investing in a standing desk, parking your car in the furthest spot, using resistance bands while you watch your favorite show, or having walking meetings.

VILPA

A study published in Nature last fall (Association of wearable device-measured vigorous intermittent lifestyle physical activity with mortality) showed the positive effect of vigorous intermittent lifestyle physical activity (VILPA, or vigorous NEAT) in lowering risk of death. VILPA is brief and sporadic (1-2 minutes at a time) that occurs throughout the day. This study used wrist trackers (accelerometers) to continuously record movement in over 25,000 sedentary people who didn’t exercise and walked once or less a week. In measuring their activity, however, researchers found that nearly 90% of them engaged in VILPA (as defined by increased heart rate on their trackers) doing daily activities, like climbing stairs, carrying heavy groceries, and running to catch a bus.

Researchers concluded that just a minute or two of VILPA 3-4 times a day was associated with a 40% lower risk of death over seven years compared to people who didn’t engage in any vigorous activity. VILPA three to four minutes, two or three times a day, was associated with lower all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality risk. For these health benefits, however, VILPA needs to be consistent, with short bouts of heart rate-increasing activity every day. The authors concluded that VILPA in nonexercisers showed beneficial health benefits similar to vigorous activities in exercises. VILPA requires minimal time commitment and no preparation or equipment. Since most adults over 40 don’t engage in vigorous exercises, and may find structured exercise unappealing or not feasible, regular bouts of intense activity woven into daily routines may provide an alternative for those unable or unwilling to exercise.

HIIT

In a study published just over a month ago in JAMA (Association of Preoperative High-Intensity Interval Training With Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Postoperative Outcomes Among Adults Undergoing Major Surgery), researchers tied preoperative High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) to lower postoperative complications. Preparing for surgery is like preparing for an intense physical competition since inflammation and tissue healing after surgery increases oxygen consumption by up to 50%. HIIT rapidly increases cardiovascular fitness (CRF), even in the very limited preoperative time frame. Approximately 160 minutes of HIIT resulted in a 10% increase in CRF. By increasing CRF before surgery, patients essentially trained their bodies for the anticipated increased demands of surgery. In this study, those who engaged in HIIT preoperatively had better outcomes, including lowering hospital length of stay and improved quality of life.

How to get more Strength Training

A New York Times article by journalist Danielle Friedman (A Low-Pressure Guide to Make Strength Training a Habit. For real this time.) provides some guidance on how to begin strength training – including a 20-minute routine to get you started. Friedman recommends starting small, keeping your workout simple, and setting achievable goals (some strength training is better than none). Exercise physiologists recommend 20 minutes of strength training twice a week or 10-15 minutes three times a week. If you aren’t doing any strength training, this may be your lofty goal. Depending on time and desire, you may set a SMART goal to train once a week for the first month and then gradually increase toward the ultimate goal. You don’t need to go to a gym or rely on a lot of equipment. Strength training can be done with weights, kettlebells, resistance bands, and your own body weight.

Learn proper form to avoid injury (and therefore the need to stop your strength training before you really get started). You can do this by scheduling a few sessions with a personal trainer (who can also help you create a plan). Some people find they are more successful when they strength train earlier in the day (it can be hard to motivate a weary body to pick up weights).

Experts suggest increasing motivation by “temptation bundling” – pairing something you love (listening to specific music or a gripping audiobook) with something you find challenging or don’t particularly love but want to do (lift weights). Bundling works best when you only allow yourself to indulge in that particular pleasure only when you are working out (like saving the most intriguing book for when you are strength training only).

How to Know if you are Doing What you Need to Do to be More Fit

The best way to get a baseline of your physical fitness (and to later measure your success) is through an exercise physiologist. These professionals can assess your cardiovascular fitness by measuring your VO2 max, and determine your musculoskeletal fitness by testing your strength, endurance, flexibility, and power. If, however, you don’t have access to this type of testing, there are ways to estimate your fitness level on your own. In a 6 part series on fitness, Andrew Huberman interviews an exercise science expert, Andy Galpin, Ph.D. While I haven’t listened to the whole series (yet) the first episode (How to Assess & Improve All Aspects of Your Fitness) explains how to do your own comprehensive assessment of your current fitness level so that you can develop an ideal fitness program tailored to you.

While I’ve written (somewhat exhaustively) about many aspects of physical fitness in this three-part blog, don’t be overwhelmed. The takeaway is really quite simple: move your body more.

I’m a fan of acknowledging the small WINS throughout t out the day- NEAT fits this perfectly. It’s a great reminder that simple things can be meaningful, like parking my car a far distance. I always appreciate that you offer several options so that I can pick the one that works for me at this time, while also knowing that I can add more when I’m ready.

LikeLike

Thanks Cindy – small wins are big wins!

LikeLike