A month or so ago, a patient questioned me “off the record” about whether I thought the medical community was “taking it a bit too far” and “over-reacting” in wearing face shields and masks. With coronavirus deaths escalating and hospitals loaded to capacity, I was shocked by his question. Fortunately he couldn’t see much of my expression through mask and shield and distance. I calmly told him that no, I did not. I explained how I wished more people were doing the same. I shared how I worry every day about contracting the virus and spreading it to my immune-compromised patients or bringing it to the nursing home where I care for the elderly or to my family.

As it would turn out, my family brought it home to me.

The day after Christmas my husband Paul developed a fever and chills, followed quickly by a cough. On Sunday he and my youngest son got tested. Both were positive. While I suspect Paul got sick from helping a debilitated family member, we will never really know how the virus entered our home and took over, rendering my husband hostage for weeks.

I was impressed by how fast the contact tracer reached out to inform me that I had to quarantine. Even before the diagnosis was confirmed, I was wearing a mask and sleeping just outside our bedroom as an extra precaution after Paul’s exposure. At the end of our conversation, the contact tracer asked if we needed any food or other supplies. I assured her that we did not but thanked her and expressed how happy I was that this question was asked. I often wondered how some of my patients managed quarantining without any warning or chance to prepare. At least we had holiday leftovers.

Over the next week, friends and family checked in with well wishes, some bringing food. One neighbor delivered milk, eggs and homemade soup to our porch and another brought a bag overflowing with fresh fruit and yogurt. Our friends from the city surprised us daily, leaving an assortment of food, drinks, medicine and other essentials on our porch as they blew kisses through the glass pane. On New Year’s Eve, a family friend brought us traditional Persian New Year soup so we could celebrate by sharing a meal together, even while apart.

After Paul tested positive, I gave up my sleeping spot outside our bedroom and dragged a mattress into the upstairs office, knowing I would spend many nights apart from him. At the time, I didn’t realize this would stretch into weeks. Since I wasn’t sick myself, I tried to work from home. Limited internet and poor cell service left me frustrated and stressed. I felt sorry for myself and couldn’t imagine other professionals working under these conditions. At lunch (and occasionally when I had a minute between patients), I’d check in with Paul, who basically stayed in bed.

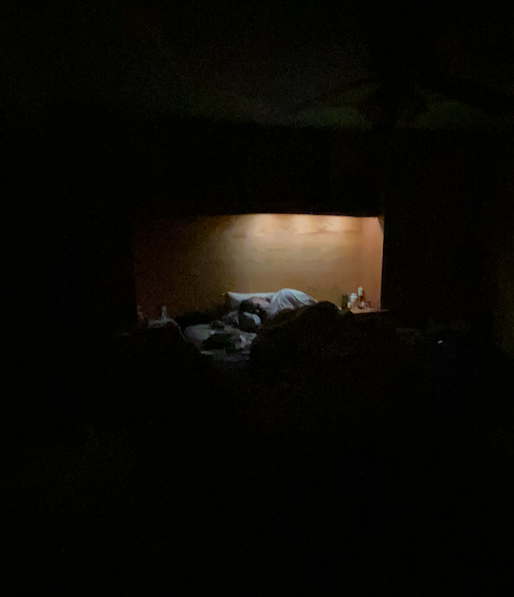

Orion never developed symptoms, but Paul got very sick. For the first few days I peeked in from the door, trying to check on him without disturbing him. His still form was piled under blankets in the dark. In addition to coughing, I heard frequent grunts and groans from the bedroom. When I’d ask how he was feeling, he replied in short, barely audible grunts. I interpreted these as “leave me alone,” and so for the first week, I let him be. He slept most of the day and didn’t seem to really need my help. I felt like I was bothering him while he was trying to rest. (Paul later confided that he intentionally pushed me away, closing himself off for my protection: The only thing that could be worse than how I was feeling would be for you to feel that way, too, and for me to be unable to do anything about it.)

Doctors like to fix things, and I convinced myself that first week that there was nothing for me to do anyway. The virus had to run its course. As I read these words now, I see that I was essentially acting as if this was “just like the flu,” something I frequently counseled skeptical patients against. Later that night, my mother, a retired nurse, told me that it was good that Paul had me to take care of him. I assured her that he would have been better off with a nurse, and she readily agreed. I thought it unhelpful (and maybe unwise) to sit masked at his bedside, risking contracting the virus myself from his unpredictable, sudden, forceful coughs. In truth, I didn’t want to watch his fitful sleep or hear his moans when he changed position – I didn’t like to see him so vulnerable. I felt useless. He just didn’t need me.

I would soon find out I was wrong.

Paul tried his best, in his debilitated state, to take care of himself. He set a timer so he could take ibuprofen and acetaminophen around the clock. Despite this, his fever regularly spiked above 104 and his body aches were so severe that they scared him. I wasn’t aware of his fear at the time, but only learned of it later when I overheard him talking to his sister. “I just imagined that I was pulling in all the pain from mom,” he’d said (Paul’s mom had a milder case). He explained that this gave him a small sense of control over what he described as “the worst nightmare.” When I shared this with my own sister, a hospital nurse, she told me that the COVID patients she cared for were very still, not moving at all. It was as if any small shift might exacerbate their pain and make it unbearable.

The next day, after I finished seeing patients through telemedicine, I removed my noise-cancellation headphones to check on Paul. From my upstairs work space, I heard spastic, unremitting coughing. I ran down the stairs to find Paul, pale and exhausted-looking. His eyes were full of suffering. I realized how wrong I had been, naively believing this virus just had to run its course.

Paul needed me. If nothing else, he needed my professional medical reassurance. Because he is knowledgeable in so many subjects, I often forget that he didn’t actually study medicine. When I suggested that I might need to take him to the emergency room, he confided that he didn’t want to go. He was afraid that if he went to the hospital, he’d end up on a ventilator. That this thought worried him had never even crossed my mind. I quickly reassured him that it was very unlikely that he would ever need that kind of respiratory support. Since the pandemic began, I’d comforted hundreds of anxious and fearful patients that most people will be okay. This was what Paul needed to hear. Because he was generally healthy, he simply couldn’t make sense of his severe and unremitting symptoms. He presumed the worst.

I did my best to explain what I thought was happening, something I should have done from the very start (and something that would have come naturally to me if he were actually my patient). Paul couldn’t keep up with his increased fluid needs – everything passed right through him and he threw up what little he managed to eat. He was also sweating from the high fevers. This made him weak and lightheaded. I explained that he was likely dehydrated and a trip to the ER for IV fluids could help him feel much better.

I then made him go outside in below-freezing temperatures so I could (as safely as possible) listen to his lungs. He couldn’t take a deep breath without coughing and wincing in pain. I put my stethoscope to his bare back and listened. Instead of smooth air movement, I heard crackling. It sounded like pneumonia. I called the on-call doctor on a Sunday morning, something I haven’t done in over 20 years. The doctor started Paul on antibiotics and advised us to go to the ER if things got any worse. Paul was relieved to have a further explanation for why he was feeling so bad as well as a plan to treat it.

More than my medical expertise, though, Paul needed my loving presence. I had failed him the first week of his illness, but I vowed to change that. My mother had been texting me all day for an update. When I finally got around to calling her that evening, I burst into tears. I was really worried about him. I told her that he was coughing so hard while I was working right upstairs but that I couldn’t hear him with my headphones on. She immediately stated the obvious: stop working. In truth, I hadn’t considered it before. I was working from home so I deluded myself that I was available if he needed me. Clearly, I was wrong and my mother was right. Paul needed me full time, at least for a few days.

I didn’t think Paul would even notice my new availability (he was out of it much of the time). But the day after I stopped working to be a devoted caretaker, he tearfully thanked me for coming back to him. While I’d thought I was leaving him alone to recover quietly on his own, he just felt alone.

Mercifully, the aches gradually reduced but his other symptoms fluctuated wildly. Every time I sent positive messages to concerned friends and family, he’d take another turn for the worse and I’d have to send another update. The uncertainty was unnerving and the constant worry made us both weary. At times, we just cried.

11 days into his illness, Paul was still spiking fevers near 104. He still wasn’t able to keep anything down and was weaker. He only got out of bed to stagger to the bathroom and when he did he’d sometimes stumble. It was time to go to the ER. I called the charge nurse at the hospital to let her know that I was bringing my husband in, who was positive for COVID. I walked him in to triage and waited with him in reception until they whisked him away. I tried to suppress my fear that they might keep him, that it could be a long time until I saw him again.

I spent about an hour in the parking lot texting Paul and updating family members when we both decided I should just go home. A trip to the ER is never a speedy endeavor, especially in a pandemic. Our home was in much-need of cleaning, specifically the bedroom which had served as a sick ward for over a week. I drove away.

At home, I slipped on the noisy medical respirator I’d brought from work and heavy-duty gloves and tore his sheets off the bed. I opened the back door to air out the room and ran the vacuum. I had barely finished washing the sheets when Paul texted me to let me know that he would be discharged in the next 20 minutes. I dropped what I was doing (the hospital was about 25 minutes away) and left immediately.

When I was still about 10 minutes out, he texted that he was heading toward the exit. I drove as fast as I dared, not wanting him to wait outside too long. As I neared the hospital, I had to shift over to the left lane to accommodate a man shuffling alongside the desolate back road. It was Paul.

I did a U-turn and pulled over. He got in the car, coughing and wheezing. Seeing him looking so frail, I felt guilty that I’d ever left the parking lot in the first place. I thought: “What were you thinking? You just got out of the ER with pneumonia!” One look at his face, though, changed my outrage to concern. He explained that there were three people in the waiting room and he didn’t want to risk giving them the virus, so he went outside. When I pointed out that he was nearly a mile from the hospital, he admitted that his judgment might be a little impaired.

Miraculously, despite his walk in the cold air, he seemed better that night. Just as hope rose, though, it came crashing down. The next morning he was bad again and his oxygen level was 85%. Despite the bitter temperature, I opened the bedroom door to let in fresh air and brought him an albuterol inhaler. I quickly got dressed, anticipating another visit to the ER. Fortunately, by the time I was ready, his oxygen levels improved. Soon after, though, he spiked a temperature above 103.

The supportive “treatment” of COVID at home is exhausting, chasing symptoms before they rage out of control again, waiting helplessly by to see if the intervention worked. Paul had every single symptom listed on the CDC website except a sore throat. On day 12 he was still alternating acetaminophen and ibuprofen every 4 hours (at 3-4 pills each dose, this alone added up to 2 dozen pills a day). Any attempt to spread out his doses resulted in spiking fevers, which increased his headaches and body aches and, therefore, his misery. Although I was reluctant to make him swallow even more pills, I added a medication to protect his stomach from the high doses of ibuprofen he was taking.

Paul took a pill for nausea. He took guaifenesin twice a day so he could breathe out of his nose (sinus pain was the symptom that gave him the greatest discomfort in the beginning). He was on an antibiotic for the pneumonia and prednisone for the bronchospasm. He took Vitamin D, not only since it is winter in upstate New York, but also because low levels may be associated with worse outcomes in COVID. At dinner, he took an aspirin and two routine medications. I finally made a spreadsheet to help keep track of his medication regimen, which amounted to almost 40 pills a day. I really don’t know how people who are not medically trained manage this at home.

Day 13 began with a worrisome oxygen level of 77% that quickly came back up with his inhaler. Despite his breathing, later that day he said, “I feel human.”

On day 14, we had oxygen delivered up our desolate road in frigid temperatures at 10 PM. Paul had a much better night.

On day 15, his temperature had improved significantly as did his appetite. I shamelessly emailed good friends of ours (who happen to be excellent cooks) and requested they make an extra portion of their next meal for Paul. They delivered a box for the family.

On day 16, Paul had his first meal out of bed. I abandoned my normal seat right next to him to sit at the opposite end of the table so we could eat together, at a distance. This was the first meal we shared since Christmas.

On day 17, Paul puttered around the house! I went in to my office for half the day.

On day 18, I got my second COVID vaccine and picked up an incentive spirometer to help Paul exercise his lungs.

On day 19, Paul got up and made breakfast (a normal occurrence that hadn’t happened since Christmas breakfast). We took a short walk around our yard (the first time he’d been outside). We walked slowly. I made him stop and check his oxygen level after a few minutes. It was 80%. We headed back into the house to rest. Just before we went inside, I tucked my masked face down and ducked into his arms and held him for a few seconds. We hadn’t hugged in twenty days, not that I was counting.

On Day 20, Paul was released from quarantine. I hugged him for real and shed my indoor mask, hopefully for good. The next day we drove to the food store together – a routine event that was both monumental and joyful. It will be a long time (hopefully never) before I take time spent together for granted.

For most of Paul’s illness, I was too busy worrying about his current situation to consider the future. But every now and then, my mind went where I didn’t want it to go. I thought of the “long-haulers” who battle symptoms for months. I hoped there was no permanent lung damage since Paul hasn’t finished winter-hiking the 46 Adirondack high peaks yet. Before he got sick, he was planning to run again. I hoped that our long biking excursions and kayaking adventures weren’t behind us. We have big dreams, Paul and I.

Despite being quarantined in a home with two positive cases, I know I am lucky. My personal challenges were minimal – keeping the wood stove going, researching how to cook the pork Paul bought for Sunday dinner (before he got sick) so it didn’t go to waste, trying to figure out what mixes with rye whiskey in the absence of my bartender and wishing I had given in and let Paul teach me how to make my morning espresso. I missed the delicious meals Paul cooked for us. (A dear friend texted ,“You must be starving! Who is cooking?” to which I confessed that I’d made a big salad to accompany our hot dogs that very night). We did not suffer, with loving friends and neighbors who delivered meals and groceries.

More importantly, my family didn’t have to worry about how to pay for care. We have jobs that worked around us. Paul’s work never once pressured him about his time away. I didn’t worry that when I called in to work I might be fired and we’d lose our health insurance.

I never felt alone.

And, despite COVID invading my home, I tested negative three times – making me even more confident that mask-wearing and hand-washing and social-distancing really work. Part of it must be the precautions we took before we even knew Paul was sick. I also like to think some credit goes to the vaccine I received the day prior to Paul’s exposure – who knows?

One thing I do know for sure, though. Caring for a sick loved has made me immensely grateful. I am so thankful to the friends who delivered food, waving through the closed door. I eagerly await the chance to reciprocate their love. I’m also awed by Paul’s doctor, who not only texted to check on us regularly but also arranged for oxygen to be delivered after hours, on a Friday evening. I am forever grateful to the driver who braved our rural dirt road to deliver it a on bitter cold night. He probably saved us from a hospitalization.

I also know that if a loved one ever needs caregiving again, I won’t let them push me away in their pain and suffering. I will overcome my feelings of inadequacy and show up anyway. I will remember that when I finally became the caregiver Paul needed, we both felt better.