“I can’t breathe.”

More than any others, these three words propel healthcare workers to action. Witnessing someone struggling to breathe causes a surge of adrenaline, giving strength and endurance for whatever must be done. Obviously healthcare workers aren’t the only ones moved by this desperate, panicked plea for help. It’s hard to justify, then, why it took America so long to respond with the heroic measures that systemic racism and violence demands.

Black Lives Matter.

Black Lives Matter.

At least we say they do. After the 2017 white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, multiple physician groups issued policy statements declaring hate crimes to be a public health concern. Yet in 2018, hate-crime violence reached a 16-year high.

And then in 2019, for the first time ever, Black Americans reported being more fearful of being shot by police than of being killed in their own communities. Their fear is not unwarranted. According to DeRay Mckesson, civil rights activist and a leading voice in the Black Lives Matter movement, in a third of all cases where American citizens are killed by a stranger it is by a police officer.

We know that police brutality is overwhelmingly targeted at Black Americans. According to an article this week in Time, a black person is killed by the police more than every other day. From 2015-2019, police killed roughly 1000 Americans each year with Black Americans nearly three times as likely to die than whites even though they are 1.3 times less likely to be armed. Despite a marked drop in all crime in March and April of this year from coronavirus quarantining, the number of deaths at the hands of police remained unchanged from last March and April.

The medical community has long known that, in addition to bodily harm and death, violence inflicts psychological damage that leads to chronic health problems. After George Floyd’s public murder, doctors’ organizations again voiced their concern – racism is a public health crisis and police brutality must end.

The American Board of Family Medicine wrote: We know that racism kills. Sometimes it is direct, as we have observed over the past week, but more often than not, it kills by exacerbating the underlying health disparities in our country as evidenced by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The president of the American Academy of Family Physicians wrote: The elimination of health disparities will not be achieved without first acknowledging racism’s contribution to health and social inequalities. This includes inequitable access to quality health care services.

The American Academy of Pediatrics wrote: The killing of George Floyd is the latest evidence that racism persists and that much work remains to address inequalities in the nation’s education, employment, judicial and health care systems. Children exposed to discrimination can develop toxic stress that affects their physical, mental and behavioral health throughout their lives.

The American Medical Association wrote: Physical or verbal violence between law enforcement officers and the public, particularly among Black and Brown communities where these incidents are more prevalent and pervasive, is a critical determinant of health and supports research into the public health consequences of these violent interactions.

I wish I could write that the medical community has always stood by black Americans. The history of injustice, though, is deep-rooted. When America finally emancipated slaves it was with minimal social support – as if simply cutting the shackles was enough to allow a weary, broken people to survive much less thrive. The Freedman’s Bureau was established just before the end of the Civil War as a temporary agency charged with helping former black slaves and poor whites through providing food, housing and medical aid. It was unable to carry out the high ideals of its mission successfully in part due to a shortage of money and people. A more significant barrier, though, was the politics of race and discrimination.

According to former Harvard College Dean Evelynn M. Hammonds, “The inequalities of the health system were built in from the beginning.” She elaborates that the health of Black Americans was barely improved after they gained freedom because of difficulties getting even the basic amenities of food, shelter, and clothing. A disproportionate number succumbed to the smallpox epidemic, supporting arguments that black people were better off as slaves – blacks were a weaker race, dependent on whites for their survival. This argument was particularly dangerous since it provided a rationale not to waste resources on a race destined to die off.

With minimal monetary investment and few doctors willing to treat them, blacks received inferior care at home or, if they were lucky, in hospital basements. Some courageous people fought to change this shameful legacy, though. Rebecca Lee Crumpler (a name I’d never heard during my training) was the first black woman to become a doctor in the United States, caring mostly for poor women and children. After the Freedman’s Bureau was established, Dr. Crumpler moved to Richmond, Virginia to do missionary work treating freed slaves. Not surprisingly, despite her intelligence and bravery, she was a victim of both racism and sexism.

Dr. Crumpler did not believe that black people were physically inferior to whites. She understood that the disproportionate morbidity and mortality among the black population was the result of systemic discrimination. People without access to clean water and food inevitably became sick. And, when they did, they were often denied appropriate medical attention. To combat this, Dr. Crumpler published A Book of Medical Discourses with the hope of educating nurses and empowering mothers with basic medical knowledge so they could treat their families and wouldn’t need to rely on a system that had repeatedly failed them.

The American healthcare system also has a shameful history of experimentation on blacks. James Marion Sims, heralded as the “Father of Modern Gynecology,” invented the vaginal speculum and pioneered gynecological surgical techniques by practicing on black slaves. His specialty was the treatment of painful fistulas formed between the uterus and vagina, a relatively common complication of childbirth in the 19th century. According to a June 2020 article in History, Sims perfected his technique by performing experiments on slaves without the use of anesthesia. He believed the popular conviction that black people didn’t feel pain – a notion that shockingly persists today according to a study from the University of Virginia published in the April 4, 2016 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Sims took ownership of the slave women until their treatment was completed, patching them up so they could perform their childbearing duties for their masters again. Sometimes this required multiple surgeries. According to his own autobiography (where he proudly claimed to never have a lack of subjects to operate on), Sims performed 30 operations over a four year period on a 17-year-old slave named Anarcha to perfect his method. Sims was also known to perform unsuccessful experiments on black slave children. He believed that blacks were less intelligent than whites because their skulls grew too quickly around their brains. He reportedly used a shoemaker’s tool to pry the bones of slave children apart to loosen their skulls and allow for more growth.

The cruelty of the American medical system’s treatment of blacks persisted well after the 1800s, as evident in The Tuskegee Syphilis study. Research began in 1932 and continued up until 1972(!) when a public outcry finally forced its end after concluding that the black men involved had never given informed consent. According to the CDC website, the Public Health Service and Tuskegee Institute had initially proposed a six month project as an attempt to record the natural history of syphilis with the hopes of eventually justifying treatment programs for blacks. 40 years later the treatment never came.

The black subjects of the study were told that they were being treated for “bad blood,” a local term used to describe a multitude of ailments including syphilis, anemia, and fatigue. In exchange for participating, the men received free medical exams, meals, and burial insurance. The painful truth, though, is that the men were never actually treated for syphilis even though penicillin became the drug of choice for the disease in 1947. They were never given the option of quitting the study even though highly effective treatment was widely available.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr said, “Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhumane.” We must be better by now, right? Not much.

Discrimination increases the risk of chronic health problems like depression, heart disease, high blood pressure and diabetes causing disproportionate disability and death in black communities. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, despite being recognized and documented for many years, health care disparities not only persist in black communities but in some cases have actually worsened. Blacks (as well as American Indians and Alaska Natives) have worse outcomes than whites across most health measures including physical and mental health, birth risks, infant mortality (which is twice as high), HIV/AIDS and others.

We can now (shamefully) add coronavirus to the list of health issues disproportionately impacting black lives. An article this week in Time illustrates how the coronavirus “laid bare the nation’s racial inequities.” Although about 13% of the population is black, the CDC reports that 22% of those infected with the virus and 23% of all deaths are Black Americans. This isn’t because blacks are a “weaker race” but is rather the expected outcome of an unfair fight.

Black Americans are at a great disadvantage (for all health problems) because of country’s failure to acknowledge and improve social determinants of health (including food access, quality housing, educational opportunities, employment, green space, financial security). Even more heartbreaking is the failure of our health care system to provide adequate access to Black Americans. I hope that the outrage demonstrated by protests around the country serves as a catalyst to (finally) drive expansion of health coverage and improve accessibility to these underserved communities.

In a society whose medical institutions (charged with improving the health and wellbeing of its citizens) fall so short in caring for the black community, there can be no doubt that racism is endemic. The large majority of Americans agree. Pew Research Center reported that 2/3 of Americans felt that expressions of racism became more common during Trump’s presidency. Time wrote that the “President has turned the Oval Office into an instrument of racial, ethnic and cultural division.” They cite his infamous comment about “good people on both sides” at the Charlottesville white-supremacist march, his waging war with NFL players peacefully protesting police brutality, his description of African nations as “sh*thole countries” and his suggestion to a black American Congresswomen that they “go back” to where they came from.

At the start of the George Floyd protests Trump borrowed words spoken in 1967 by Miami’s controversial and aggressive Police Chief Walter Headley. “When the looting starts, the shooting starts.” As protests spread, Trump referred to demonstrators as “thugs” and threatened them with “vicious dogs” as well as the deployment of “thousands and thousands” of “heavily armed” military personnel. The grounds surrounding the White House were cleared out using tear gas and brute force for his photo op at the Church.

Tear gas is a chemical weapon prohibited for use in warfare by various international treaties but used by law enforcement and the military for riot control. In addition to causing eye pain and temporary blindness, tear gas irritates the mucous membranes of the, nose, mouth and lungs causing sneezing, coughing, shortness of breath – all actions known to promote the spread of coronavirus. Through the use of tear gas police have increased coronavirus exposure to a population that is statistically the most likely to be infected and die.

Despite a possible increase in coronavirus infections, however, protests will likely save lives, especially if they lead to police reform. It’s well past time Americans started listening to the black activists who have researched, protested, and testified about this deplorable stain on American culture. Black Americans report that policies about “use of force” are one of the most important determinants of police brutality. Not surprisingly, areas of our country with stricter regulations (for example banning chokeholds, verbal warnings before shooting, and requiring de-escalation techniques as well as exhaustion of all other alternatives before the use of deadly force) have lower numbers of deaths attributed to police. Communities where these policies are stricter are safer and the police themselves are safer. Changing these policies is one of the easier things that our country can do since they are mostly controlled at the local level – authority resides with the mayor or Chief of Police.

Activists also tell us that the other major contributor to police brutality is found in the protection police receive from unions. Officers who are disciplined for brutality are frequently rehired by their districts, perpetuating the cycle of violence. Building pressure (through protests, for example) to overcome the lack of political will to reform police unions will likely be more challenging and will take longer than regulating the use of force. Still, it is a worthwhile pursuit because it will save lives. Areas of America where mental health first responder programs have been instituted to assist with 9-1-1 calls also show a reduction in police violence.

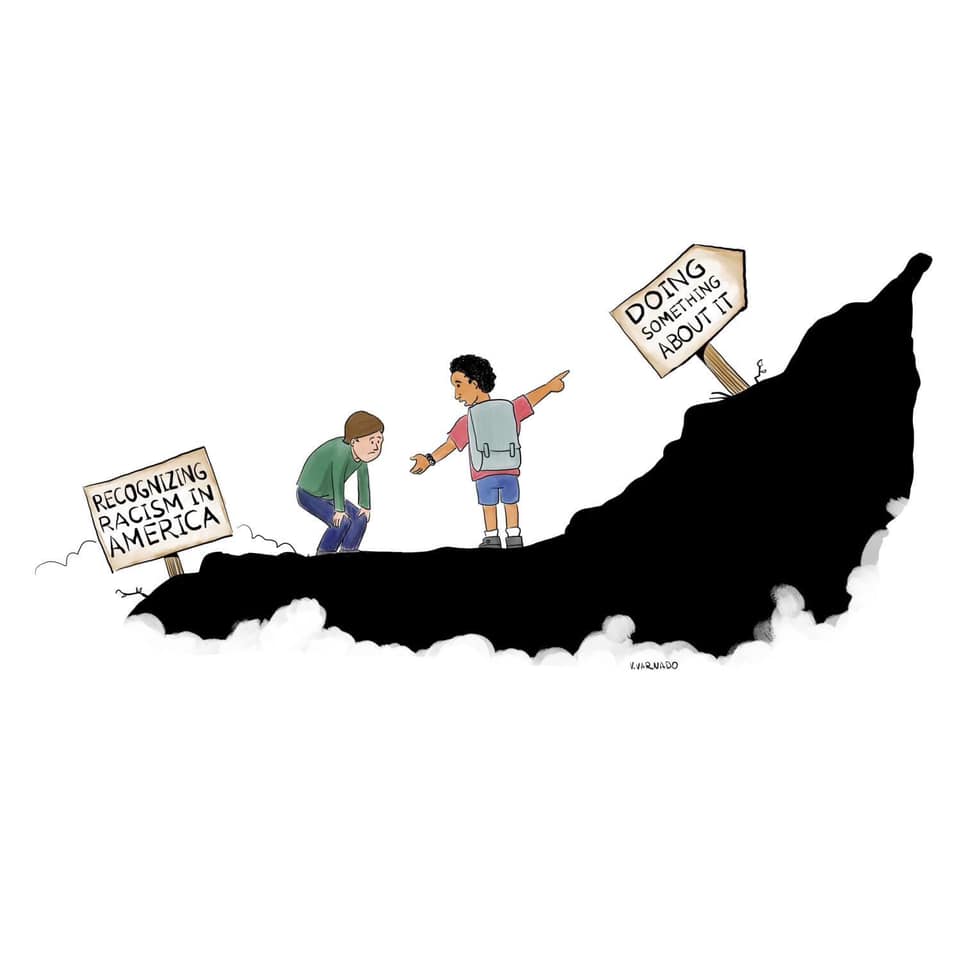

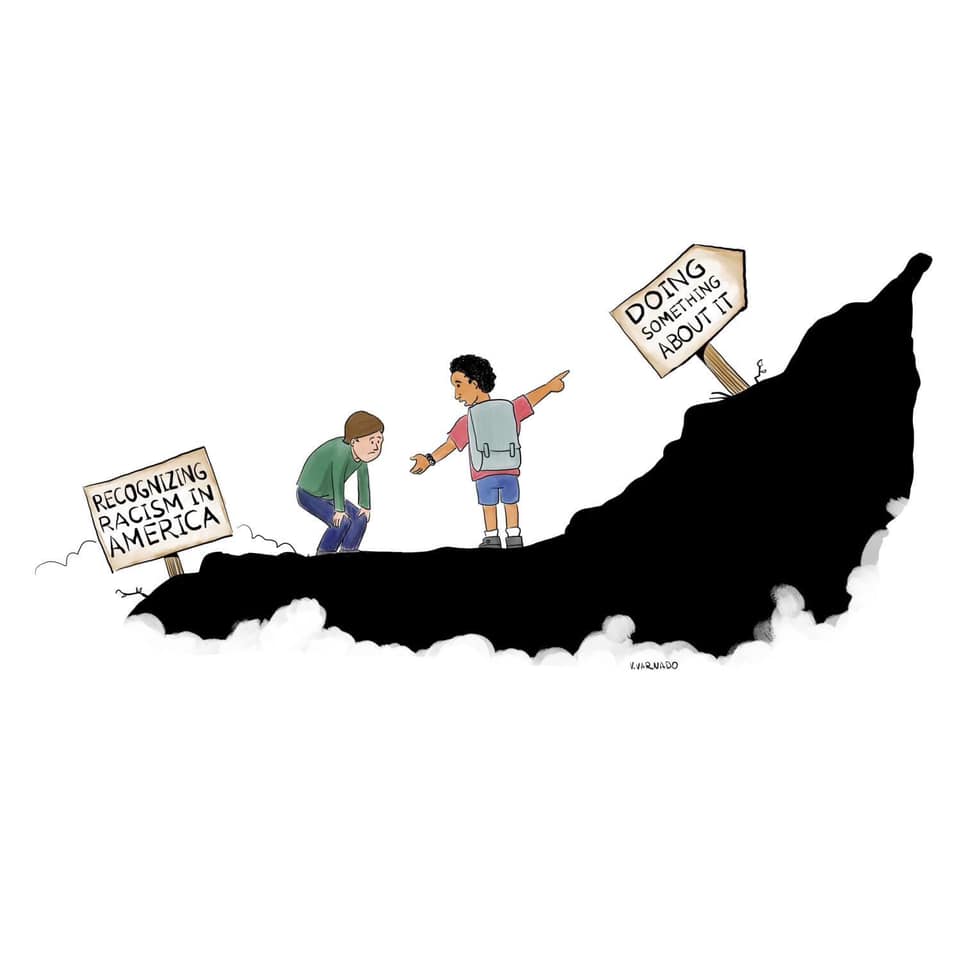

It’s important to voice it: Black Lives Matter. But it’s well past time to actually do something about it. Become an ally (or, better yet, become like my sister Ally who always fights the good fight). Educate yourself. Don’t expect your black friends and family to take on this enormous feat – they are likely exhausted from years of trying. This document, compiled by Sarah Sophie Flicker and Alyssa Klein in May 2020 is a good starting place: bit.ly/ANTIRACISMRESOURCES.

Be an Ally

If you are white, acknowledge your privilege. In 1990 Peggy McIntosh (then associate director of the Wellesley Collage Center for Research on Women) came to a realization about racism while researching male privilege. She recognized that what she’d been taught was only half of the story – that racism put other people at a disadvantage. She had not been taught to recognize white privilege as something that puts her at an advantage.

McIntosh wrote, “White privilege is like an invisible weightless knapsack of special provisions, maps, passports, codebooks, visas, clothes, tools, and blank checks. Describing white privilege makes one newly accountable.” I recommend reading her paper “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack.” http://convention.myacpa.org/houston2018/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/UnpackingTheKnapsack.pdf.

Here are a few points she made:

-

- If I should need to move, I can be pretty sure of renting or purchasing housing in an area which I can afford and in which I would want to live.

- I can be pretty sure that my neighbors in such a location will be neutral or pleasant to me.

- I can go shopping alone most of the time, pretty well assured that I will not be followed or harassed.

- I can be pretty sure of having my voice heard in a group in which I am the only member of my race.

- I can arrange to protect my children most of the time from people who might not like them.

- I do not have to educate my children to be aware of systemic racism for their own daily physical protection.

- I can swear, or dress in second hand clothes, or not answer letters, without having people attribute these choices to the bad morals, the poverty or the illiteracy of my race.

- I can be pretty sure that if I ask to talk to the “person in charge”, I will be facing a person of my race.

- If a traffic cop pulls me over or if the IRS audits my tax return, I can be sure I haven’t been singled out because of my race.

- I am not made acutely aware that my shape, bearing or body odor will be taken as a reflection on my race.

- I can be sure that if I need legal or medical help, my race will not work against me.

- I will feel welcomed and “normal” in the usual walks of public life, institutional and social.

McIntosh concluded, “As my racial group was being made confident, comfortable, and oblivious, other groups were likely being made unconfident, uncomfortable, and alienated. Whiteness protected me from many kinds of hostility, distress, and violence, which I was being subtly trained to visit, in turn, upon people of color. In my class and place, I did not see myself as a racist because I was taught to recognize racism only in individual acts of meanness by members of my group, never in invisible systems conferring unsought racial dominance on my group from birth.” I did not see myself as a racist.

I’ve set some personal intentions for myself and I’m listing them here to be held accountable. I will listen carefully to people of color when they speak about racism. I will talk less. I will honor their feelings. Although I realize these conversations may be uncomfortable, I will not get defensive. I will educate myself and ask questions. I will acknowledge (and seek to forfeit) advantages that have been bestowed on me because of the color of my skin. I will make amends as I am able. I will be an Ally and challenge other white people to think critically about racism. I will speak up when I witness it.

“I can’t breathe.”

May these haunting words propel our society into long-overdue action. May they give us the strength and courage to do what must be done. It is never too late to change.

Black Lives Matter. At least we say they do. It’s time we actually do something about it.