Sandra sat before me, crying.

“My life was ruined by my hand injury. I’m in pain all the time. My boyfriend left because he can’t stand to be around me. He said I am miserable.”

I handed her a tissue. She was only a few years older than my oldest son and was raising two small children on her own. Her face was drawn and tired. She barely looked at me when she spoke.

I tried to offer some hope. Her life was not over, but really only beginning. In a few years her children would be starting school. Also, if she kept working at it she would finish her online degree in the next year, which could open up many more gratifying work opportunities.

She looked up at me through her tears. “I miss work a lot already. I can’t sleep. I barely function doing nothing,” she whispered.

I wanted to help Sandra’s pain. I wanted her to be able to function both at home and work. I wanted her to sleep at night so that she could care for her girls. I wanted her to have a good quality of life. I tried to treat my patients the way I wanted my own family treated. If my mother or sister ever had unrelenting pain I hoped their doctor would treat it.

Sandra was on narcotic medication for “chronic regional pain syndrome”, a very difficult condition to treat often requiring the help of specialists in pain management. Unlike the vague diagnosis of “chronic back pain”, there were visible signs of her symptoms. Her left hand was swollen and red and very sensitive to the lightest touch.

I started prescribing narcotic medication to help her sleep at night. She was working and trying to take care of her kids, something that was not easy to do alone even on a good night sleep.

As is often the case, her prescription gradually increased. She asked me if she could take one extra pill during the day if she overdid it at work. The request didn’t seem unreasonable. I certainly didn’t want her to stop working and apply for disability at her young age. I knew from experience that this would not only be bad for her self-esteem, but would not be good for her children.

Soon, though, Sandra was taking three pills a day. I found myself writing prescriptions for 90 pills a month.

I knew it was too much, but I could justify it to myself. Sandra was sort of a success story. She had a debilitating injury that usually took people out of the work force and on to disability. Sandra continued to work, take classes and care for her children.

I have read commentaries blaming America’s drug problem on doctors that make me wince. They describe doctors freely prescribing addictive drugs rather than taking care of their patients. I know there are some doctors like this, but I don’t believe it is the norm.

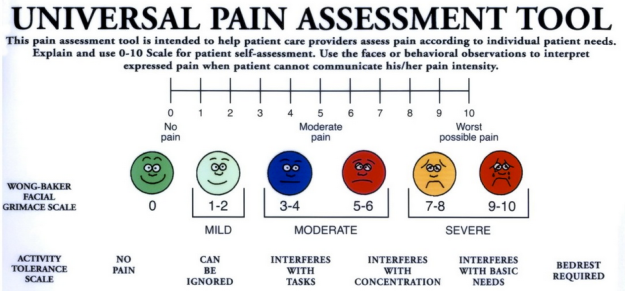

Like many of my colleagues, I was taught in residency to treat a patient’s pain as I would any other medical problem. It was implied that American doctors allowed their patients to suffer even though treatment was available. Newer long-acting drugs were developed that supposedly had less drug abuse potential. Even nurses were taught to include a measurement of pain with each patient visit as “the fifth vital sign”.

Doctors responded by stepping up their pain management strategies until very recently when the medical community changed it’s mind, leaving physicians like me feeling bewildered. I was heartbroken that in the course of trying to help people I may have contributed in some way to the current drug addiction crisis in this country.

Treating pain is not easy. There is no simple test to objectively assess the pain level of a person crumpled on the floor in the office. There is no equivalent to a “strept test” or “urine dipstick” to provide the magic number of pain. There is no way to know if the person crying in front of me just has a low pain threshold or if he is truly in excruciating pain.

Even if I had an accurate pain level, there is no straightforward algorithm for treatment as there may be for an uncomplicated urinary tract infection, for example. The fact is that people in pain don’t fit neatly into categories. There are so many non-medical factors a doctor must consider before deciding on a course of treatment. Is the patient the sole source of income for the family? Would the medication allow them to continue to work? Is there someone else in the house who may be pressuring them into obtaining narcotics? Is the patient at risk for addiction? For diversion?

There are also practical considerations. Narcotics are cheap and many other non-narcotic options are not covered by insurance. There is limited access to pain management (most of whom don’t prescribe pain medication anymore). If a patient is fortunate enough to go to pain management but treatments (such as ultrasound-guided injections) don’t help they will inevitably return back to me for medication. It’s a real mess that has made many of my colleagues question their comfort with their newfound role as law enforcer and interrogator. They question why they became doctors. I question myself sometimes.

A few weeks after this appointment a patient confided in me that Sandra was selling the medication I was prescribing.

I didn’t want to believe it and certainly couldn’t accept it as truth without any proof, but it did mean I would have to be more rigorous in my screening. I was saddened by the possibility that Sandra took advantage of my sympathetic nature. I trusted my patients until they gave me reason not to. I didn’t want to practice medicine at a cold, safe distance from my patients.

I was especially disappointed because I had gone out of my way to help Sandra in many ways over the years that she was my patient. I had written a letter to her employer urging him not to fire her when she missed too much work because of her chronic pain. I had written to her school requesting an extension on a project because of an exacerbation of her pain and the resultant difficulty concentrating. I had appealed to her insurance company for a trial of acupuncture and for approval on her medicines.

I really hoped my informant was wrong.

The next time I saw Sandra I asked if she was taking the medication as prescribed, three times a day. She nodded in confirmation. I requested that she do a urine drug screen. I explained that I had been negligent about performing this test on her in the past but that it was a routine procedure for patients on long-term controlled substances.

Did I imagine it, or did I see a flash of concern on her face?

She told me she had just used the bathroom before she came. She didn’t think she could give me a urine sample. I offered to get her some water.

I went in to see my next patient while Sandra drank the water. After a few minutes my nurse knocked on the door. “No luck with Sandra,” she whispered. I suggested my nurse bring her another glass of water.

I popped in to see Sandra again before I went in to see my next patient. She looked visibly uncomfortable. “I really don’t think I will be able to go,” she said.

“We don’t need much,” I said. I was beginning to think my suspicions would be confirmed.

The next time I passed by her room she popped her head out. “Can I talk to you for a second?” she asked. I went in and closed the door behind me.

“I didn’t actually take my medication yesterday or today because I ran out,” she said. “I was in a lot of pain so I took an extra pill for several days last week,” she continued.

I was prepared for this. Sadly, it wasn’t the first time a patient disappointed me.

“Why didn’t you tell me that when I asked if you had been taking your medication as prescribed?” I asked. She shrugged. “Even if you took your pill four times a day for the last week, you should still have some left since I only wrote the prescription two weeks ago,” I said. She had no response.

“Sandra, you know that I can’t continue to prescribe your pain medication. You broke your pain contract,” I told her. She started to cry.

“But what about my pain? You have to help me!” she cried.

“I have tried to help you,” I said as calmly as I could. I was not happy to catch her. I thought we had a good doctor-patient relationship. “I’m not actually sure that you’re taking the pain medication at all,” I said. I didn’t like confrontation but I was also angry. How could she lie right to my face with no regard to my care for her and her children over the years?

“You can’t just cut me off!” she said.

I do believe that Sandra’s hand injury caused her pain and that she probably did take the medicine at times. I didn’t have the heart to just stop it without a plan. I agreed to taper her down over the next month while I tried to get her in to see pain management and appealed to her insurance for a different medication. After this I would no longer prescribe narcotics to her.

I left the room feeling as bad as she did.

Whose fault was this? Was it Sandra’s for deceiving me and possibly selling the medicine to help make ends meet? Was it mine for prescribing the medication in the first place? Was it the insurance company’s fault since generic narcotics are cheap and are always covered while newer non-narcotic pain medications and other treatments like acupuncture, physical therapy and specialists are often not?

I knew that this was not the last I would hear from Sandra. There would likely be many calls back and forth, pleading and crying. She might ask me to forgive her, to give her one more chance.

I would need to remind myself that the drugs she was likely selling may end up in my own children’s school.

I didn’t want to be a part of the drug problem.